These 3 Houston research projects are coming up with life-saving innovations

research roundup

Research, perhaps now more than ever, is crucial to expanding and growing innovation in Houston — and it's happening across the city right under our noses.

In InnovationMap's latest roundup of research news, three Houston institutions are working on life-saving health care research thanks to new technologies.

Rice University scientists' groundbreaking alzheimer's study

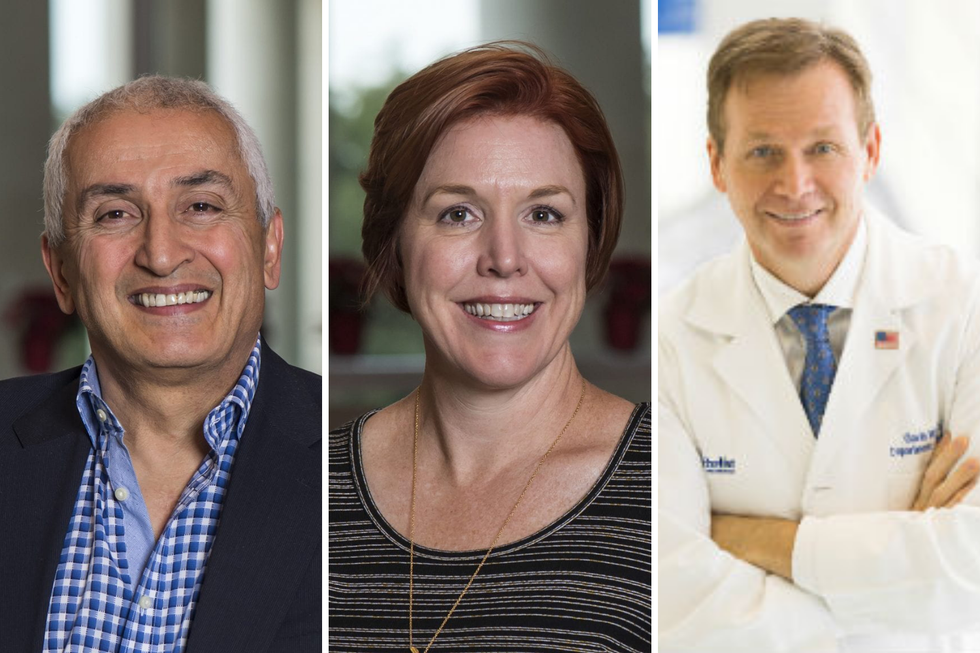

Angel Martí (right) and his co-authors (from left) Utana Umezaki and Zhi Mei Sonia He have published their latest findings on Alzheimer’s disease. Photo by Gustavo Raskosky/Rice University

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Alzheimer’s disease will affect nearly 14 million people in the U.S. by 2060. A group of scientists from Rice University are looking into a peptide associated with the disease, and their study was published in Chemical Science.

Angel Martí — a professor of chemistry, bioengineering, and materials science and nanoengineering and faculty director of the Rice Emerging Scholars Program — and his team have developed a new approach using time-resolved spectroscopy and computational chemistry, according to a news release from Rice. The scientists "found experimental evidence of an alternative binding site on amyloid-beta aggregates, opening the door to the development of new therapies for Alzheimer’s and other diseases associated with amyloid deposits."

Amyloid plaque deposits in the brain are a main feature of Alzheimer’s, per Rice.

“Amyloid-beta is a peptide that aggregates in the brains of people that suffer from Alzheimer’s disease, forming these supramolecular nanoscale fibers, or fibrils” says Martí in the release. “Once they grow sufficiently, these fibrils precipitate and form what we call amyloid plaques.

“Understanding how molecules in general bind to amyloid-beta is particularly important not only for developing drugs that will bind with better affinity to its aggregates, but also for figuring out who the other players are that contribute to cerebral tissue toxicity,” he adds.

The National Science Foundation and the family of the late Professor Donald DuPré, a Houston-born Rice alumnus and former professor of chemistry at the University of Louisville, supported the research, which is explained more thoroughly on Rice's website.

University of Houston professor granted $1.6M for gene therapy treatment for rare eye disease

Muna Naash, a professor at UH, is hoping her research can result in treatment for a rare genetic disease that causes vision loss. Photo via UH.edu

A University of Houston researcher is working on a way to restore sight to those suffering from a rare genetic eye disease.

Muna Naash, the John S. Dunn Endowed Professor of biomedical engineering at UH, is expanding a method of gene therapy to potentially treat vision loss in patients with Usher Syndrome Type 2A, or USH2A, a rare genetic disease.

Naash has received a $1.6 million grant from the National Eye Institute to support her work. Mutations of the USH2A gene can include hearing loss from birth and progressive loss of vision, according to a news release from UH. Naash's work is looking at applying gene therapy — the introduction of a normal gene into cells to correct genetic disorders — to treat this genetic disease. There is not currently another treatment for USH2A.

“Our goal is to advance our current intravitreal gene therapy platform consisting of DNA nanoparticles/hyaluronic acid nanospheres to deliver large genes in order to develop safe and effective therapies for visual loss in Usher Syndrome Type 2A,” says Naash. “Developing an effective treatment for USH2A has been challenging due to its large coding sequence (15.8 kb) that has precluded its delivery using standard approaches and the presence of multiple isoforms with functions that are not fully understood."

BCM researcher on the impact of stress

This Baylor researcher is looking at the relationship between stress and brain cancer thanks to a new grant. Photo via Andriy Onufriyenko/Getty Images

Stress can impact the human body in a number of ways — from high blood pressure to hair loss — but one Houston scientist is looking into what happens to bodies in the long term, from age-related neurodegeneration to cancer.

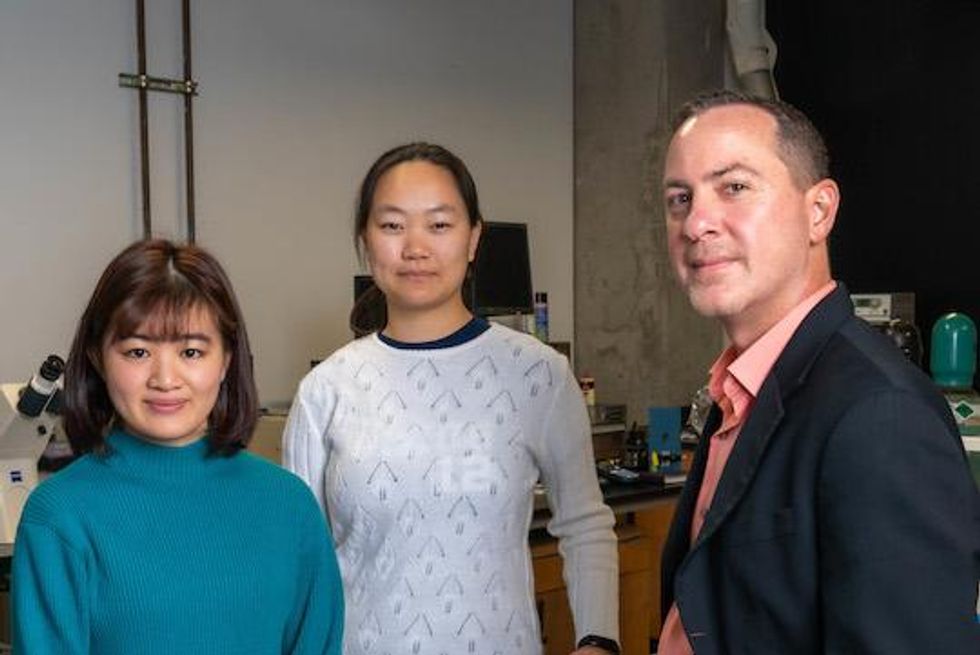

Dr. Steven Boeynaems is assistant professor of molecular and human genetics at Baylor College of Medicine. His lab is located at the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital, and he also is a part of the Therapeutic Innovation Center, the Center for Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases, and the Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center at Baylor.

Recently, the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, or CPRIT, awarded Boeynaems a grant to continue his work studying how cells and organisms respond to stress.

“Any cell, in nature or in our bodies, during its existence, will have to deal with some conditions that deviate from its ideal environment,” Boeynaems says in a BCM press release. “The key issue that all cells face in such conditions is that they can no longer properly fold their proteins, and that leads to the abnormal clumping of proteins into aggregates. We have seen such aggregates occur in many species and under a variety of stress-related conditions, whether it is in a plant dealing with drought or in a human patient with aging-related Alzheimer’s disease."

Now, thanks to the CPRIT funding, he says his lab will now also venture into studying the role of cellular stress in brain cancer.

“A tumor is a very stressful environment for cells, and cancer cells need to continuously adapt to this stress to survive and/or metastasize,” he says in the release.

“Moreover, the same principles of toxic protein aggregation and protection through protein droplets seem to be at play here as well,” he continues. “We have studied protein droplets not only in humans but also in stress-tolerant organisms such as plants and bacteria for years now. We propose to build and leverage on that knowledge to come up with innovative new treatments for cancer patients.”