3 ways University of Houston researchers are innovating brain treatments and technologies

Brain teasers

While a lot of scientists and researchers have long been scratching their heads over complicated brain functionality challenges, these three University of Houston researchers have made crucial discoveries in their research.

From dissecting the immediate moment a memory is made or incorporating technology to solve mobility problems or concussion research, here are the three brain innovations and findings these UH professors have developed.

Brains on the move

Professor of biomedical engineering Joe Francis is reporting work that represents a significant step forward for prosthetics that perform more naturally. Photo courtesy of UH Research

Brain prosthetics have come a long way in the past few years, but a UH professor and his team have discovered a key feature of a brain-computer interface that allows for an advancement in the technology.

Joe Francis,a UH professor of biomedical engineering, reported in eNeuro that the BCI device is able to learn on its own when its user is expecting a reward through translating interactions "between single-neuron activities and the information flowing to these neurons, called the local field potential," according to a UH news release. This is all happening without the machine being specifically programmed for this capability.

"This will help prosthetics work the way the user wants them to," says Francis in the release. "The BCI quickly interprets what you're going to do and what you expect as far as whether the outcome will be good or bad."

Using implanted electrodes, Francis tracked the effects of reward on the brain's motor cortex activity.

"We assume intention is in there, and we decode that information by an algorithm and have it control either a computer cursor, for example, or a robotic arm," says Francis in the release.

A BCI device would be used for patients with various brain conditions that, as a result of their circumstances, don't have full motor functionality.

"This is important because we are going to have to extract this information and brain activity out of people who cannot actually move, so this is our way of showing we can still get the information even if there is no movement," says Francis.

Demystifying the memory making moments

Margaret Cheung, a UH professor, is looking into what happens when a memory is formed in the brain. Photo courtesy of UH Research

What happens when a brain forms a new memory? Margaret Cheung, a UH professor in the school of physics, computer science, and chemistry, is trying to find out.

Cheung is analyzing the exact moment a neuron forms a memory in our brains and says this research will open doors to enhancing memory making in the future.

"The 2000 Nobel laureate Eric Kandel said that human consciousness will eventually be explained in terms of molecular signaling pathways. I want to see how far we can go to understand the signals," says Cheung in a release.

Cheung is looking at calcium in particular, since this element impacts most of cellular life.

"How the information is transmitted from the calcium to the calmodulin and how CaM uses that information to activate decisions is what we are exploring," says Cheung in the release. "This interaction explains the mechanism of human cognition."

Her work is being funded by a $1.1 million grant from the National Institute of General Medical Science from the National Institutes of Health, and she's venturing into uncharted territories with her calcium signaling studies. Previous research hasn't been precise or conclusive enough for real-world application.

"In this work we seek to understand the dynamics between calcium signaling and the resulting encoded CaM states using a multiphysics approach," says Cheung. "Our expected outcome will advance modeling of the space-time distribution of general secondary messengers and increase the predictive power of biophysical simulations."

New tech for brain damage treatment

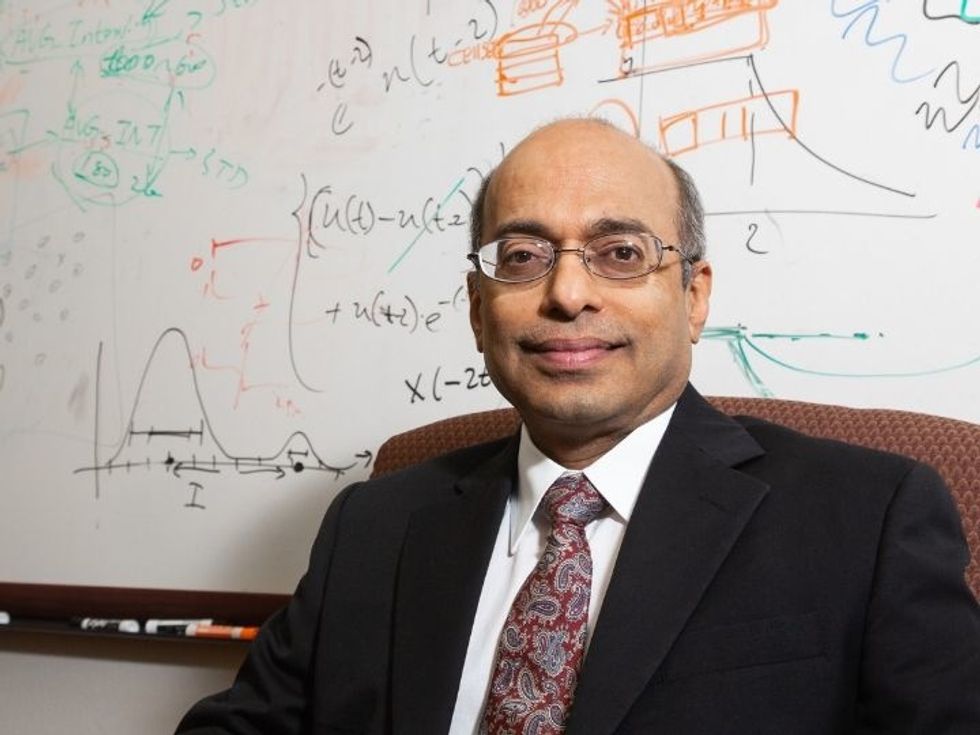

Badri Roysam, chair of the University of Houston Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, is leading the project that uncovering new details surrounding concussions. Photo courtesy of UH Research

Concussions and brain damage have both had their fair shares of question marks, but this UH faculty member is tapping into new technologies to lift the curtain a little.

Badri Roysam, the chair of the University of Houston Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, is heading up a multimillion-dollar project that includes "super microscopes" and the UH supercomputer at the Hewlett Packard Enterprise Data Science Institute. Roysam calls the $3.19 million project a marriage between these two devices.

"By allowing us to see the effects of the injury, treatments and the body's own healing processes at once, the combination offers unprecedented potential to accelerate investigation and development of next-generation treatments for brain pathologies," says Roysam in a release.

The project, which is funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), is lead by Roysam and co-principal investigator John Redell, assistant professor at UTHealth McGovern Medical School. The team also includes NINDS scientist Dragan Maric and UH professors Hien Van Nguyen and Saurabh Prasad.

Concussions, which affect millions of people, have long been mysterious to scientists due to technological limitations that hinder treatment options and opportunities.

"We can now go in with eyes wide open whereas before we had only a very incomplete view with insufficient detail," says Roysam in the release. "The combinations of proteins we can now see are very informative. For each cell, they tell us what kind of brain cell it is, and what is going on with that cell."

The technology and research can be extended to other brain conditions, such as strokes, brain cancer, and more.