Every day, important research is being completed under the roofs of Houston medical institutions. From immunotherapy to complex studies on how a memory is made, Houston researchers are discovering and analyzing important aspects of the future of medicine.

Here are three research projects currently being conducted around town.

University of Houston's potential solution to sickle cell disease

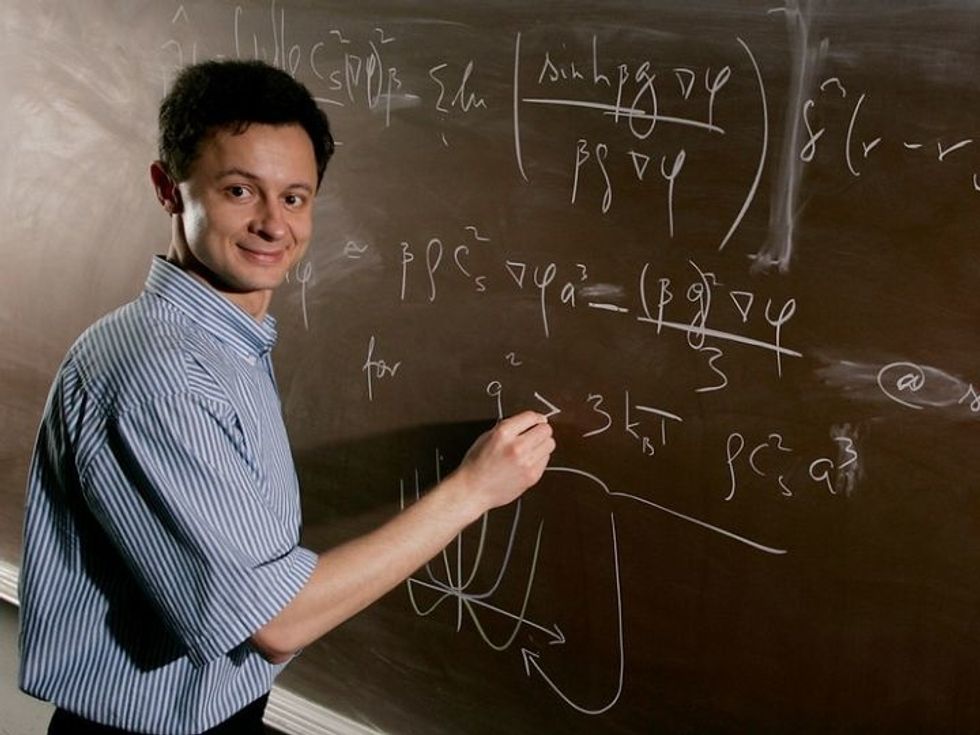

Vassiliy Lubchenko is a University of Houston associate professor of chemistry. Courtesy of UH

For the most part, sickle cells have been a mystery to scientists, but one University of Houston professor has recently reported a new finding on how sickle cells are formed — enlightening the medical community with hopes that better understanding the disease may lead to prevention.

Vassiliy Lubchenko, UH associate professor of chemistry, shared his new finding in Nature Communications. He reports that "droplets of liquid, enriched in hemoglobin, form clusters inside some red blood cells when two hemoglobin molecules form a bond — but only briefly, for one thousandth of a second or so," reads a release from UH.

In sickle cell disease, or anemia, red blood cells are crescent shaped and don't flow as easily through narrow blood vessels. The misshapen cells are caused by abnormal hemoglobin molecules that line up into stiff filaments inside red blood cells. Those filaments grow when the protein forms tiny droplets called mesoscopic.

"Though relatively small in number, the mesoscopic clusters pack a punch," says Lubchenko in the release. "They serve as essential nucleation, or growth, centers for things like sickle cell anemia fibers or protein crystals. The sickle cell fibers are the cause of a debilitating and painful disease, while making protein crystals remains to this day the most important tool for structural biologists."

Lubchenko conclusion is that the key to prevent sickle cell disease is to is to stop the formation of the initial clusters so fibers aren't able to grow out of them.

Baylor College of Medicine's immunotherapy research in breast cancer

Baylor College of Medicine researchers are looking into the complexities of immune cells in breast cancer. Getty Images

Baylor College of Medicine researchers are leading an initiative to figure out the potential effect of immunotherapy on different types of breast cancers. Their report is featured in Nature Cell Biology.

The scientists zoned in on two types of immune cells — neutrophils and macrophages — and they found frequency differed in a way that indicated potential roles in immunotherapy.

"Focusing on neutrophils and macrophages, we investigated whether different tumors had the same immune cell composition and whether seemingly similar immune components played the same role in tumor growth. Importantly, we wanted to find out whether differences in immune cell composition contributed to the tumors' responses to immunotherapy," says Dr. Xiang 'Shawn' Zhang, professor at the Lester and Sue Smith Breast Center and member of the Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine, in a news release.

Further exploring the discrepancies between the immune cells and the role they play in tumor growth will help better understand immunotherapy's potential in certain types of breast cancer.

"These findings are just the beginning. They highlight the need to investigate these two cellular types deeper. Under the name 'macrophages' there are many different cellular subtypes and the same stands for neutrophils," Zhang says. "We need to identify at single cell level which subtypes favor and which ones disrupt tumor growth taking also into consideration tumor heterogeneity as both are relevant to therapy."

Rice University, UTHeath, and UH's memory-making study

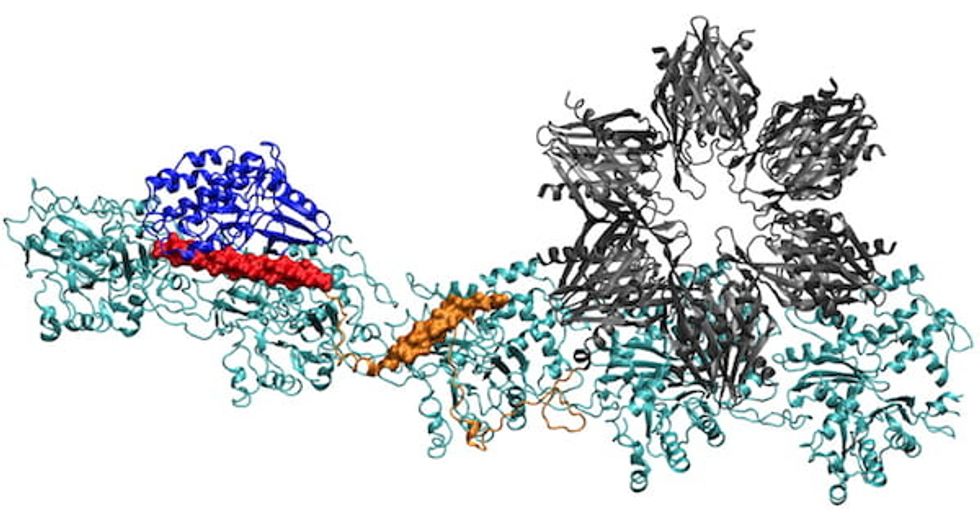

Researchers from all corners of Houston are diving into how memories are made. Courtesy of Rice University

When you make a memory, your brain cells structurally change. Through a multi-institutional study with researchers from UH, Rice University, and the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, we now know more about the way memories are made.

When forming memories, three moving parts work together in the human brain — a binding protein, a structural protein and calcium — to allow for electrical signals to enter neural cells and change the molecular structures in cognition. The scientists compared notes on how on that binding protein works.

The team's study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Peter Wolynes, a theoretical physicist at Rice, UH physicist Margaret Cheung, and UTHealth neurobiologist Neal Waxham worked together to understand the complex process memories experience in the process of being made.

"This is one of the most interesting problems in neuroscience: How do short-term chemical changes lead to something long term, like memory?" Waxham says in a release from Rice. "I think one of the most interesting contributions we make is to capture how the system takes changes that happen in milliseconds to seconds and builds something that can outlive the initial signal."

Apple doubles down on Houston with new production facility, training centerPhoto courtesy Apple.

Apple doubles down on Houston with new production facility, training centerPhoto courtesy Apple.